|

|

04/10/2014 |

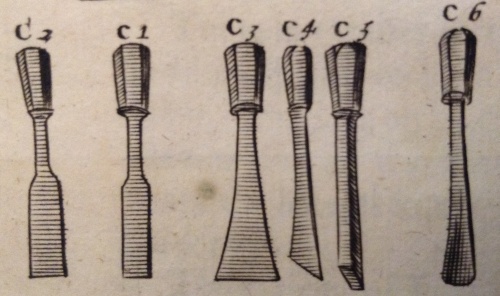

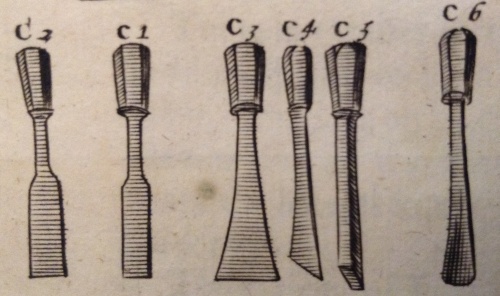

Click here for the start of this series. The mortise chisel illustrated in Moxon's 1678 "Mechanicks Exercises" (c5) was in all probability made by a London smith who specialized in tools, but otherwise had a blacksmith shop pretty much the same as any other blacksmith. A waterwheel to power a trip hammer and bellows would be a wonderful thing, but at that time it wasn't obvious that he would have one. The tool would have been forged from wrought iron and a tiny piece of blister steel would have been welded onto the top for the cutting edge. At this time it would have been cost prohibitive to put a section of brass pipe around the base of the tool (continuous brass pipe wasn't available on the market yet), a ferrule as they would be called later, to keep the handle from splitting when you put a lot of lateral force on the tool. The solution to all of this for mortise chisels, and in fact all the chisels of the time as seen in the engraving, were wide, thick handles that would bear down and spread the force of the blow on a wide flange called a "bolster" that was placed below the tang. Click here for the start of this series. The mortise chisel illustrated in Moxon's 1678 "Mechanicks Exercises" (c5) was in all probability made by a London smith who specialized in tools, but otherwise had a blacksmith shop pretty much the same as any other blacksmith. A waterwheel to power a trip hammer and bellows would be a wonderful thing, but at that time it wasn't obvious that he would have one. The tool would have been forged from wrought iron and a tiny piece of blister steel would have been welded onto the top for the cutting edge. At this time it would have been cost prohibitive to put a section of brass pipe around the base of the tool (continuous brass pipe wasn't available on the market yet), a ferrule as they would be called later, to keep the handle from splitting when you put a lot of lateral force on the tool. The solution to all of this for mortise chisels, and in fact all the chisels of the time as seen in the engraving, were wide, thick handles that would bear down and spread the force of the blow on a wide flange called a "bolster" that was placed below the tang.

While the engraving in Moxon isn't to scale, we can see the basic shape of a 19th century mortise chisel start to emerge and both the bolster and handle of the mortise, along with all the other chisels illustrated are faceted. Octagonal bolsters and handles were pretty common on all types early 19th century chisels but as the century wore down round or oval handles - which are easier to make, became more usual, and the bolsters on mortise chisels become oval.

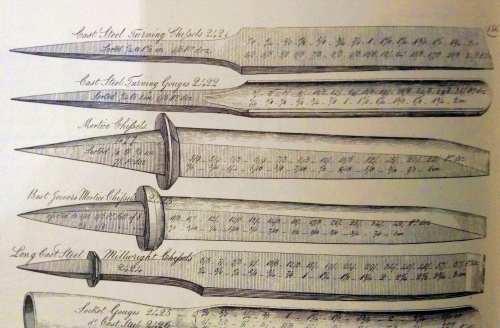

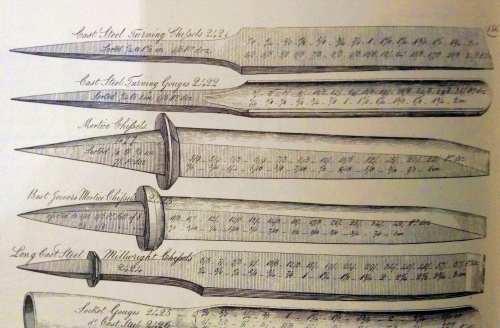

Three very important events happen in the century after Moxon. An industrial revolution massively lowered the price and availability of iron and steel, and by 1800 very high quality crucible steel (invented in 1740) was inexpensive enough to use on things other than watch springs and razors. "Cast Steel" was the trade name that was stamped on tools when they were made of crucible steel or other high carbon steels that were melted to absorb carbon, not beaten like blister steel. The second thing that happened was a network of canals sprang up all over England so it was possible for a manufacturer in for example Sheffield to find a ready market for goods in London and other commercial centers. Like today, a well capitalized business, with modern machinery, a ready source of power (water then steam), and easy distribution could decimate local smaller manufacturers. The Sheffield makers did just that. The lovely set of mortise chisels (along with all the chisels) in the 1797 Seaton chest were bought from a high end London merchant but were made by Phillip Law, a large Sheffield edge tool maker.

Law's operation would have employed dozens of men, almost all on piecework, each specializing on one operation or another. Individual craftsmen would essentially rent from Law the use of a trip hammer, forge, or grinding wheel, for the purpose of manufacture. They would probably buy their materials from Law, and then sell back the finished goods, advanced to the next stage of operation. Law's operation would have employed dozens of men, almost all on piecework, each specializing on one operation or another. Individual craftsmen would essentially rent from Law the use of a trip hammer, forge, or grinding wheel, for the purpose of manufacture. They would probably buy their materials from Law, and then sell back the finished goods, advanced to the next stage of operation.

Blacksmiths using trip hammers would first take a blank of wrought iron and draw out a tapered tang. Then the other side of the tool would be shaped, and a steel blank for the cutting edge welded in. The bolsters on Mortise chisels are too big to easily forge in and on most of the ones Ray Iles has examined the bolster is shrunk on. This is done by punching out a ring of iron, then heating it way hot. Then you pop it on the cold tang. As it cools it shrinks down and grabs the tang, never to let go. Then you can do any final forging. Finally the grinders, using big four foot wheels, clean up all the surfaces, make sure everything is tapered correctly and then you are done.

All that's needed is a handle.

The catalog illustration in the middle of this entry is from the 1845 Timmins & Sons' tools pattern book (reprinted by Phillip Walker 1994). (The curvature in the picture is because of my bad photography.) The bolster of the common mortise chisel is thin and while not octagonal is also not perfectly oval either. It's more like the rounded rectangular bolsters I have seen. The best mortise chisel has an oval bolster that is thick and chunky by comparison.

Click here for Part 1 and the introduction to this series.

Click here for Part 2 - What the Catalogs Tell Us.

Click here for Part 4 - Chisel handles.

Click here for Part 5 - How to Handle a Chisel.

|

Join the conversation |

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

Law's operation would have employed dozens of men, almost all on piecework, each specializing on one operation or another. Individual craftsmen would essentially rent from Law the use of a trip hammer, forge, or grinding wheel, for the purpose of manufacture. They would probably buy their materials from Law, and then sell back the finished goods, advanced to the next stage of operation.

Law's operation would have employed dozens of men, almost all on piecework, each specializing on one operation or another. Individual craftsmen would essentially rent from Law the use of a trip hammer, forge, or grinding wheel, for the purpose of manufacture. They would probably buy their materials from Law, and then sell back the finished goods, advanced to the next stage of operation.